- Home

- Tim Bonyhady

Two Afternoons in the Kabul Stadium Page 14

Two Afternoons in the Kabul Stadium Read online

Page 14

Two journalists on the Ariana flight succeeded in getting beyond the airport. One was Derek Williams, a New Zealand cameraman with CBS, whom Afghan officials allowed into Kabul because his passport identified him as a technician. The other was Hugh Van Es, a Dutch photojournalist on assignment for Time, who defied airport authorities by running through an open door carrying just his camera bag, finding a taxi and heading for the city. By the time he was caught, the flight to Delhi had gone, so officials decided to put him up in the Intercontinental Hotel. When officials realised that Williams was a cameraman, they put him there too. The government planned to send them back to Delhi the following day but, because snow closed the airport, the journalists stayed until 2 January, photographing and filming when they were permitted to leave the Intercontinental while waiting for their flight.

The Soviet news agency Tass was soon releasing its own photographs. On the whole, the western press rejected them as biased. But as part of providing the biggest pictorial coverage of Afghanistan, the New York Times published a few, while presenting them in such a way as to turn them against the communists. It started on 6 January with a photograph of a group of men holding copies of The Truth of the April Revolution, a newspaper just started by the Karmal government. With manifest scepticism, the Times reported that Tass’s caption was: ‘Afghan people resolutely support measures of the new leadership aimed at defending the gains of the revolution.’

Many other photographers flew into Kabul at the start of the new year. The communists turned back most of them, but two or three gained entry before 5 January, when the Soviets withdrew nearly all of their military from Kabul’s streets, confident they had the city under control and the Karmal government began issuing visas. Almost immediately, a few hundred journalists arrived, by far the biggest media contingent ever. For the 200-room Intercontinental Hotel, almost empty through 1979, the influx was a boon. The Kabul Hotel took the overflow. While the government instructed photographers and film crews not to record Soviet troops or equipment and barred them from bringing satellite dishes into the country, it let them transmit their material by plane without oversight.

The journalists immediately began hiring taxis and rented vans with Afghan drivers, testing what they could do. Conor O’Clery of the Irish Times was one of four who drove north on the Salang Highway because it was the Soviets’ main land route for bringing their forces to Kabul. The journalists were let through the many checkpoints by smiling officers. But when they turned back due to heavy snow, an officer detained them and confiscated their film. As O’Clery later admitted, ‘the great prize was…to get captured by Russian troops’. When he and his colleagues were apprehended, their ‘one thought’ was ‘what a good story we had!’

Babrak Karmal wanted the focus elsewhere: on the Pul-e Charkhi Prison outside Kabul, where thousands had been executed since the Saur Revolution. When these killings began attracting international attention in 1979, most were blamed on Hafizullah Amin as the most powerful figure in the Taraki government. After Amin had Taraki killed that September, he blamed Taraki for the executions, freed a small number of prisoners and announced he would release the names of the 12,000 killed. He stopped doing so when enraged relatives of the dead attacked officials and thousands of demonstrators demanded more details. Soon he resumed the imprisoning and killing.

Karmal sought to legitimise his installation by Moscow by demonstrating that he had ended this reign of terror. His first public statement deplored the ‘imprisonment, banishment, forced exiles, inhumane and even barbaric tortures, martyrdoms and massacres… under the Hangman Hafizullah Amin’, whom he identified as an ‘agent of US imperialism’. When the English-language Kabul Times resumed publication on New Year’s Day as the Kabul New Times, all its photographs, apart from portraits of Afghanistan’s new leadership, were of Pul-e Charkhi Prison. Some revealed ‘the means of torture and strangulation’ in its ‘chamber of horrors’; others were of those immediately freed by the government as part of its promise to release all political prisoners.

When the government admitted foreign journalists, it immediately invited them to Pul-e Charkhi to witness the release of most of the remaining prisoners on 6 January. Despite heavy snow, many Kabulis went too. ‘Today, the iron gates of the dreadful Pul-e Charkhi Prison swung open to let out 2073 inmates to be hugged joyously and tearfully by thousands of men, women and children from their respective families, relatives and friends’, the Kabul New Times announced. The government continued five days later when, by its account, the only political prisoners still in Pul-e Charkhi were a few members of the royal family and some supporters of the late Prime Minister Mohammad Maiwandwal, incarcerated since 1974. After the communists freed about 120 inmates, some of the crowd began trying to force their way into the prison in search of family or friends, believing they might still be incarcerated.

What followed has been much contested. The Kremlin maintained that soldiers simply fired shots in the air. Western journalists claimed a civilian and a soldier died when a thousand Kabulis stormed the prison, shouting ‘Russians get out’ and ‘Death to Russians’, and freed a dozen inmates. Photographs taken by Michel Lipchitz of Associated Press, Hans Paul of Agence France-Presse and Henri Bureau of the Sygma agency suggest that far fewer protesters entered the prison and that the soldiers eschewed violence. They show young Afghans climbing the prison’s five-metre-high iron gates, despite soldiers standing on the other side. In one photograph, a gate is open, a protester still on it, while dozens pour into the yard. Other photographs show members of the crowd within the prison grounds trying to lift their fellows to cell windows or even scaling a pipe to reach higher windows to discover who was still inside. The most evocative image is of two windows: a hand waving behind the bars in one, a hand waving through the bars in the next.

Weekly magazines lagged in their reportage, but those that specialised in photojournalism paid most to secure the best images, then published them larger, on better quality paper, in colour on their covers and usually black and white inside. When Gamma sold François Lochon’s photographs, it was not clear when others would follow, so the price was high. Paris Match, which made a business of publishing scoops, paid a record 60,000 francs for the French rights. Many other magazines, including Newsweek in the United States, Stern in West Germany, Oggi in Italy, Cosmos in Columbia and An-Nahar in Lebanon bought the rights for their countries. Even when these magazines did not publish before their local rivals, Lochon’s photographs gave them the edge, especially his prime image: a Soviet armoured personnel carrier against the backdrop of a sign, in both English and Dari, ‘Afghan Tourist’.

Because it had other stories in train, Match took over a fortnight to publish: Lochon’s photographs did not appear until 18 January. But Match still treated them as a scoop, since nothing like them had been seen in France. It also made more of them than any other magazine, devoting most pages to Afghanistan. Its cover image of three Soviet soldiers in a tank, bought by Lochon from his French contact, was inscribed ‘Photographs out of Russian Kabul’. Inside was a ten-page spread titled ‘The only photographs out of Afghanistan’, dominated by Lochon’s work. While a few western observers understood that the Kremlin sent in its troops reluctantly to prop up a failing client state with a relatively modest force, most identified the Soviets as ‘invaders’ set on extending their empire to the Indian Ocean if not the Persian Gulf. ‘Kabul under the Boot’, declared Match. ‘Have the Russians gone wild?’ asked Stern. Recognising that the decade-long era of Détente between Moscow and Washington was over, Newsweek emblazoned its cover, ‘Back to the Cold War’.

PART 2

CHAPTER 15

Shooting in Afghanistan

The Kremlin hoped its military operation in Afghanistan would be over in a few weeks. Instead, the conflict grew. Anti-Soviet sentiment played a part. New covert US funding, which Saudi Arabia immediately eclipsed, was even more significant. On 28 December 1979, President Carter ordered the supply of ‘l

ethal military equipment’ to the rebels, despite warnings from American diplomats that empowering the mujahideen would have ‘negative human rights implications’ due to the ‘subjugation of women to a life of exclusion’. Early in January 1980, the first shipment of Lee Enfield rifles for the rebels reached Pakistan, followed by Chinese-made anti-tank rockets and anti-aircraft guns. For months, it had been a matter of debate whether the fighting in Afghanistan amounted to a war. With the arrival of Soviet troops and the start of the American and Saudi arms pipeline, there was no doubt.

The communists soon sought to curb international scrutiny. A week after the fundamentalist government in Tehran evicted all American reporters in mid-January 1980, Kabul decided to do the same, accusing the Americans of ‘inventions and insinuations’ designed ‘to increase tensions…and disrupt the normal life of the Afghan people’. Then it expelled some non-Americans working for US media groups and required the remaining foreigners to employ ‘guides’ or minders and to seek daily approval for what they planned to do. In mid-February the government announced it would evict all foreign journalists, photographers and cameramen.

Russian writer Aleksandr Prokhanov drew on his own experience in A Tree in the Centre of Kabul, the first novel about the war, published in both Russian and English in 1982. The book’s protagonist, Volkov, is a journalist staying in the Kabul Hotel early in 1980 when protests against the communists were growing. When he looked out a window, Volkov saw ‘a file of Afghan soldiers, carbines in hand, escorting people in baggy trousers with their hands up’. Just as a western journalist would have done, Volkov took ‘the lens cover off his camera and focused it on the convoy, but one of the soldiers noticed this, and aimed his carbine at him’, perhaps assuming he was a westerner but also recognising that, regardless of nationality, Moscow did not want images of resistance to communist rule.

The first big protest was a general strike, organised partly through clandestine leaflets known as night-letters, sometimes topped by a drawing of three rifles pointing from the Qur’an’s opened pages. The strike was also incited by crude posters that called on Afghans to rebel and the ‘sons of Lenin’ to leave. While some shopkeepers needed no persuasion to shut their stores on 21 February, others did so under duress. That night, ‘Allahu Akbar!’, God is Great!, could be heard across Kabul as men and boys chanted from rooftops, many using loudhailers, microphones, stove-pipes and tin cans as amplifiers. The following day, a huge crowd, including some women, took to the streets urged on by loudspeakers from dozens of mosques. Again they chanted ‘Allahu Akbar!’ They also carried green flags. Before long, fighting broke out. Because of the communists’ media exclusion, the only western reporter to witness this insurrection was Swiss journalist Andreas Kohlschütter for the German newspaper Die Zeit, and he did not carry a camera. Kohlschütter identified an uncoordinated uprising involving just a few snipers with old rifles, suppressed by Afghan troops with tanks and heavy machine guns and Soviet pilots flying Mi-24 ‘Hind’ helicopter gunships. The Karmal government maintained that its forces only began to shoot on sight after they were attacked with hand grenades and heavy machine guns supplied by the United States and Pakistan and there was extensive destruction and looting. The government acknowledged it imprisoned many protesters and held some at length, while soon freeing more than fifteen hundred, a mark of the scale of the unrest.

Protests continued into mid-1980 largely led by schoolgirls—their first major display of militancy since the May Day rally photographed by Laurence Brun in 1972. Anahita Ratibzad, who sought to ‘awaken the political consciousness of Afghan women’ as Minister for Education, was a target because of her relationship with Karmal. When the students did not deride Ratibzad as his ‘prostitute puppet’, they called on her to ‘leave Afghanistan, go and sleep with Brezhnev’, then the Soviet General-Secretary. When the communists responded with force, they killed a seventeen-year-old student called Nahid. She may have been shot while holding a wounded fellow student in her arms, or climbing atop a Soviet tank, or trying to fire a captured machine gun—the many different accounts all identify Nahid as a martyr. When members of the Revolutionary Association of Women of Afghanistan fled to Pakistan, they put her photograph on the cover of their magazine.

Tass also fixed on Afghan women, but its images were intended to suggest a very different Kabul. One, published by Match, which provided the greatest magazine coverage, showed four smiling women teachers at a Kabul lycée wearing stylish western clothes without headscarves. Tass expected this photograph—in many respects a successor to Brun’s three miniskirted women in the Shahr-e Naw—to demonstrate the communists’ commitment to female emancipation. But a soldier was in the background. As the Soviet media published no images of the Soviet force in Afghanistan for more than ten weeks, and then used images that suggested its mission was purely peaceful, Match focused on the soldier in the photograph of the four teachers as evidence of Afghanistan’s militarisation.

More images came from foreign photographers who entered Kabul purporting to be tourists or carpet dealers and, if identified as reporters, were sometimes allowed to stay at the Intercontinental with minders. Italian photographer Romano Cagnoni got big spreads in Match and London’s Sunday Times magazine after he visited not only Kabul but also Kandahar, Herat and Mazar-e Sharif, sometimes using a concealed camera, disguised as an Afghan. As the western press delighted in reports that Soviets in Kabul were always at risk of being attacked, the Sunday Times captioned one of Cagnoni’s photographs as a Soviet couple ‘wisely’ shopping ‘with a handbag and an AK-47 automatic rifle’. Yet as the Times also recognised, misinformation about the Soviet presence in Afghanistan was rife and there was a dearth of ‘anything approaching detailed confirmation’ of the many reported killings of Soviets in Kabul.

Match, itself, showed how Soviets were enjoying Kabul without fear after one of the magazine’s photographers, Jack Garofalo, visited Microrayon—a high-rise complex conceived by the Soviets in the 1960s, which grew to be 381 blocks containing 9500 apartments, swimming pools and a cinema. While these apartments were intended to bring modernity to Afghans, they were increasingly occupied by the Soviets from the start of 1980, prompting some second-hand clothes dealers from the Carter Bazaar to establish stalls there. Their stock ranged from miniskirts and flared trousers to Hells Angels’ jackets. Garofalo photographed one of their customers, a Soviet woman in a sleeveless top, smiling for the camera.

With few exceptions, the western press decried the Soviets’ actions in Afghanistan, identifying them as aggressors. Commentators on the left joined in this condemnation. Critique of Washington was almost non-existent. Jill Tweedie of the Guardian was exceptional in highlighting the double standard of the US in ‘heaping abuse’ on Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini for his ‘treatment of women, while proclaiming total support for the rebels of Afghanistan who are, to a man, Ayatollahs in the making’.

The western press was particularly interested in atrocities allegedly committed by the communists. The weekly magazine published by the Parisian newspaper Le Figaro carried photographs of a young woman with terrible facial injuries said to have been inflicted by a phosphorous bomb, and a crying boy said to be the sole survivor after his village was razed by napalm. But there were always questions about the authenticity of these images and the associated reports, while there was no question about the authenticity of the many images of executions carried out by mujahideen. They started with a sequence of photographs taken northwest of Kandahar in mid-December 1979—part of the long tradition of perpetrators recording their killings. United Press International received the photographs in January 1980 from the ‘Islamic Party of Afghanistan’—most likely, one of the Hezb groups—and many newspapers and magazines in Europe and the United States then published them. The victims were one of the mujahideen’s prime targets: teachers employed by the government, whom the mujahideen claimed were vehicles for communist indoctrination.

One photograph showed three mujahideen po

inting Kalashnikovs at the heads of two teachers, who were crouching on the ground, blindfolded. A second showed one of these men being ‘interrogated’, his head on the ground and the rest of his body raised with his feet strapped to the front of a vehicle. A third showed this man dead on the ground with one of the mujahideen posing with his Kalashnikov at point blank range. Newsweek captioned it ‘A Rising Tide of Vengeance’, at least partly legitimating such executions while also suggesting that savagery was to be expected of Afghans. The New York Times titled it ‘Shooting in Afghanistan’, without further comment.

Moscow’s Literaturnaya Gazeta had already used a photograph of a turbaned, bearded Afghan with a dagger in his mouth to identify the mujahideen as primitive and barbaric. As further evidence, the Gazeta carried the photograph of the crouching men, whom it claimed were paraded before American journalists, then shot for teaching girls. By mid-1980, the Soviets had included this photograph in one of their first books about the war published in Russian and reproduced it in another book published in English with a view to an international market. ‘Yes, we take no prisoners. Yes, we are killing unfaithful teachers,’ the Soviets quoted a mujahideen representative in New York as saying. In 1983 one of the foremost Soviet postermakers, Viktor Koretsky, used this photograph as the basis of one of his last posters, which he made with fellow artist Vladimir Sokolov as part of a series about Washington’s part in fuelling conflict in a range of countries including El Salvador and Nicaragua. Koretsky and Sokolov titled their poster, ‘Afghanistan: Transoceanic Bullet’, incriminating Washington in the killing.

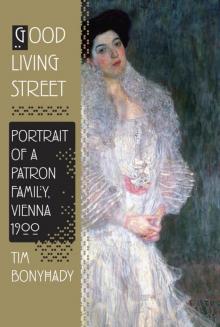

Good Living Street

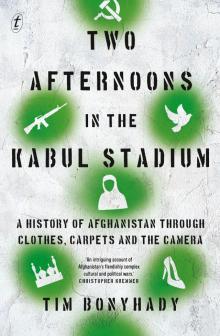

Good Living Street Two Afternoons in the Kabul Stadium

Two Afternoons in the Kabul Stadium