- Home

- Tim Bonyhady

Good Living Street

Good Living Street Read online

ALSO BY TIM BONYHADY

Images in Opposition:

Australian Landscape Painting, 1801–1890

The Law of the Countryside: The Rights of the Public

Burke and Wills: From Melbourne to Myth

Places Worth Keeping: Conservationists, Politics and Law

The Colonial Earth

Copyright © 2011 by Tim Bonyhady

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books,

a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada

by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of

Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bonyhady, Tim, [date]

Good Living Street : Portrait of a Patron Family, Vienna 1900 /

Tim Bonyhady.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN: 978-0-307-90681-6

1. Gallia family. 2. Art patrons—Austria—Vienna—Biography.

3. Jews—Austria—Vienna—Biography. 4. Gallia family—Art patronage. 5. Vienna

(Austria)—Biography. I. Title.

N5252.G35B66 2011 709.2’243613—dc22 [B] 2010053160

www.pantheonbooks.com

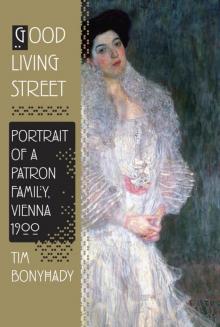

Jacket image: Portrait of Hermine Gallia, 1904, by Gustav Klimt. National Gallery,

London, UK/The Bridgeman Art Library International

Jacket design by Carol Devine Carson

v3.1

For Bruce

Contents

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

List of Illustrations

The Gallia Family Tree

I HERMINE

Introduction

1 Klimt

2 God

3 Gaslights

4 Family

5 Galas

6 Pictures

7 Rooms

II GRETL

1 Diaries

2 Tango

3 Love

4 War

5 Hoffmann

6 Death

7 Sex

8 Marriage

III ANNELORE

1 Memory

2 Austro-fascism

3 Anschluss

4 Visas

5 Subterfuge

6 Loss

7 Capture

IV ANNE

1 1939

2 Aliens

3 Correspondence

4 Eric

5 Return

6 Dispersal

7 Restitution

8 Identity

Color Plates

Notes

Index

Illustrations

ill.1 Wohllebengasse 4, c. 1913.

ill.2 Emil Orlik, Gustav Mahler, 1903.

ill.3 The postcard sent by Theobald Pollak and Alma and Gustav Mahler to Hermine, July 1903.

ill.4 Ferdinand Andri, Moriz Gallia, 1901.

ill.5 Gustav Klimt, Hermine Gallia, 1903–1904.

ill.6 The Klimt portrait of Hermine with two of Koloman Moser’s cubic chairs in the Klimt Kollektiv at the Secession, 1903.

ill.7 Gustav Klimt, Beech Forest, 1903.

ill.8 Hermine, aged about sixteen, c. 1886.

ill.9 One of Hermine’s many merit certificates.

ill.10 The Gallias and the Hamburgers, 1903.

ill.11 Moriz and Hermine, after being married in Vienna’s main synagogue, 1893.

ill.12 Moriz and Hermine kiss on the steps of Adolf and Ida Gallia’s villa, Baden, c. 1898.

ill.13 Erni with one of his wet nurses, 1895.

ill.14 Hermine with Gretl in her arms and Erni on a table, 1897.

ill.15 Käthe and Lene, 1901.

ill.16 Moriz with Erni on his shoulders and Hermine with Gretl on her lap, c. 1898.

ill.17 Hermine dressed for going out, wearing her best pearls.

ill.18 A page from Gretl’s third diary, March 30, 1916.

ill.19 The program for the Parsifal seen by the Gallias in Bayreuth, 1912.

ill.20 A letter from Klimt to Moriz accepting an invitation to dinner at the Schleifmühlgasse.

ill.21 Hermine’s photograph of Klimt, taken by the Madame d’Ora studio of Dora Kallmus, c. 1908.

ill.22 Koloman Moser, Sweet Bowl, 1903.

ill.23 Moriz and Hermine’s summerhouse in Alt Aussee.

ill.24 The ground-floor entrance to Wohllebengasse 4, designed by Franz von Krauss.

ill.25 The boudoir in the Gallia apartment.

ill.26 The smoking room in the Gallia apartment.

ill.27 The salon in the Gallia apartment.

ill.28 Eleven-year-old Gretl, 1908.

ill.29 Gretl, around the time of her two ball seasons.

ill.30 Eighteen-year-old Gretl.

ill.31 One of the Gallias’ war glasses.

ill.32 Klimt’s funeral at the Hietzing cemetery, February 9, 1918.

ill.33 Lene, Hermine, Käthe, and Gretl, late 1917 or early 1918.

ill.34 Erni and Mizzi, 1921.

ill.35 Gretl and Paul, 1921.

ill.36 Annelore, aged three, 1925.

ill.37 Annelore in her sailor suit and pearls, 1931.

ill.38 The Klimt portrait of Hermine and some of the Hoffmann furniture from the salon crammed into Käthe’s apartment in Vienna’s Third District, c. 1938.

ill.39 Annelore in her ball dress, Landstrasser-Hauptstrasse, March 1938.

ill.40 Annelore, September 1938.

ill.41 Gretl and Annelore as photographed in Brisbane by the Telegraph, January 4, 1939.

ill.42 Paul’s passport when he escaped the Nazis by illegally entering Belgium without a visa, 1939.

ill.43 St. Vincent’s College, Sydney, run by the Sisters of Charity, 1939.

ill.44 Käthe and Anne, Sydney, 1945.

ill.45 Gretl, Sydney, Christmas 1949.

ill.46 The Grail, including Anne, performing in Sydney in 1941.

ill.47 Paul, Toulouse, February 1948.

ill.48 The Bonyhadys, 1944.

ill.49 Eric and Anne, Sydney, January 1948.

ill.50 Gretl, Kathe, Anne, Bruce, and Tim in the apartment in Sydney, Christmas 1967.

ill.51 Anne, Canberra, 2002.

ill.52 The book stamp by Fritzi Löw showing Hermine and Moriz as a young courting couple.

COLOR PLATES

ill.53 The poster by Heinrich Lefler for Auer von Welsbach’s Gas Glowing Light Company.

ill.54 Ferdinand Andri, The Gallia Children, 1901.

ill.55 Carl Moll, Beethoven House, Heiligenstadt, 1903.

ill.56 Ernst Stöhr, Moonlit Landscape, 1903.

ill.57 Carl Moll, In the Gardens of Schönbrunn, c. 1910/1911.

ill.58 Giovanni Segantini, The Evil Mothers, 1894.

ill.59 The sideboard designed by Adolf Loos, 1903.

ill.60 Moriz’s inkstand, designed c. 1911 by Josef Hoffmann.

ill.61 Michael Powolny’s ceramic version of Klimt’s The Kiss, c. 1907.

ill.62 Josef Hoffmann, Design for Boudoir, 1915.

ill.63 Josef Hoffmann, Design for Smoking Room, 1915.

ill.64 Josef Hoffmann, Two Vases and a Pair of Goblets, 1915 or 1916.

ill.65 Carl Witzmann, Bowl, 1912.

ill.66 Josef Hoffmann, Work Table and Two Chairs, 1913.

ill.67 The copy of Der Ewige Jude, or The Eternal Jew.

THE GALLIA FAMILY

Click here to view a larger image.

I

HERMINE

Introduction

Nineteen thirty-eight was a good year to be a mover in Vienna. As tens of thous

ands fled the city following the German annexation of Austria, the Nazis seized their businesses, required them to pay punitive departure taxes, prevented them from converting their remaining money into foreign currency, and stole much of their art. The refugees were usually able to leave with their other household goods, however, because the Nazis were eager to maintain the pretense that Austria’s Jews were leaving voluntarily, and they wanted other countries to take them. The result was a surge in demand for movers in a city where it was common to rent the same apartment for life.

Vienna’s leading newspaper, the Neue Freie Presse, did not need to report on this new economy built on persecution that led many movers to employ more workers and some to become specialists in the refugee trade. The newspaper’s advertising columns told the story. Before the Anschluss, or annexation, that March, each edition of the Presse included at most one small advertisement from a mover, and more often contained none. Within a fortnight of the Anschluss, the Presse often carried three notices from movers quick to exploit the new market. By late April the newspaper carried up to seven of these advertisements. At the end of May, eleven.

The most remarkable consignment to leave Vienna belonged to two sisters—one unmarried, the other divorced, both unknown beyond the small circles in which they moved in Viennese society. Dr. Käthe Gallia, one of the first generation of women graduates of the University of Vienna, had abandoned her work as a chemist more than a decade earlier to become the manager of a family company that sold gas stoves. Her sister, Margarete Herschmann-Gallia, known as Gretl, had briefly been married to a Viennese leather merchant, Dr. Paul Herschmann. Like most married women of her class, Gretl had never worked.

Käthe was among the Nazis’ first victims. Her job went first. Then the SS and Gestapo raided her apartment and imprisoned her. When they finally released her almost two months later, Gretl and she decided to escape Austria with Gretl’s sixteen-year-old daughter, Annelore. While the United States of America would have taken them, the sisters chose Australia because other members of the family were headed there. By the start of November 1938, they were ready to join the fifty thousand who had fled Austria since the Anschluss. As Gretl and Käthe had all the necessary permits and approvals, they looked forward to a relatively simple departure. Once their movers packed up their apartments, they would take the train to Switzerland.

The sisters did not count on Kristallnacht, the pogrom ordered by Joseph Goebbels that erupted across the newly expanded German Reich in the early hours of the tenth of November and was more violent in Vienna than almost anywhere else. In all, the Nazis murdered at least twenty-seven Viennese Jews, severely injured another eighty-eight, and took nearly sixty-five hundred into custody, while looting more than four thousand shops and almost two thousand apartments and setting fire to almost all the city’s synagogues and prayer rooms. The one exception was the main synagogue in the First District, which the Nazis left because its torching would have engulfed other buildings and because they needed the synagogue’s records to determine who met their definition of a Jew.

When Gretl, Käthe, and Annelore realized a pogrom had started, they feared they would be among those whom the Nazis targeted. And even if they managed to escape the violence, would they be forced to flee empty-handed? They need not have worried. Their movers, who had started work a day or two before Kristallnacht, continued as usual on the tenth and eleventh of November, enabling Gretl and Annelore to leave on the twelfth and Käthe to follow on the fifteenth. As the Nazis terrorized Jews across the city, the movers swaddled the Gallias’ furniture in blankets and wrapped their silver, glass, and ceramics in layers of tissue paper, ready for shipment around the globe.

Their containers included every conceivable household and personal item, ranging from chandeliers to doormats, cake molds to binoculars, lace and linen, skates and skis, letters and diaries, invoices and receipts. Rather than take one piano, Gretl and Käthe left with two: an upright and a grand. Their paintings included portraits, landscapes, seascapes, still lifes, genre subjects, a streetscape, and an interior. Each of their three sets of silver cutlery included more than 150 pieces. The biggest of their three display cabinets was more than five feet wide and almost six and a half feet high. Their main set of bookcases was nearly twenty feet long.

The sisters had inherited some of these objects from their uncle Adolf Gallia and his wife, Ida, who, in an era when only three in every hundred Viennese owned their own homes, occupied the grandest apartment in their own immense building on Vienna’s renowned Ringstrasse. Almost everything else came from the sisters’ parents, Moriz and Hermine, who lived just beyond the Ringstrasse in Vienna’s Fourth District on the Wohllebengasse. Although named after Stefan Edler von Wohlleben, who was Vienna’s mayor at the start of the nineteenth century, Wohlleben—or “good living”—evoked the area’s character a century later. While Gasse literally means “lane” or “alley,” the Wohllebengasse was so wealthy, spacious, and elegant that it was more like “Good Living Street.”

The family was accustomed to buying the finest products, the best brands, the most prestigious labels. Just as the dinner service that Gretl inherited from her aunt Ida was one of the earliest sets of Flora Danica, the celebrated hand-molded, hand-painted porcelain decorated with Danish plants made by Royal Copenhagen, so the grand piano she inherited from her mother, Hermine, was a Steinway. Their furs included chinchilla and sable stoles and a sealskin mantle. But the paintings, furniture, silver, ceramics, and glass once owned by Moriz and Hermine were their most remarkable possessions. Almost all were from the turn of the century, when Vienna was among the world’s most dynamic cultural and intellectual centers, one of the cities vital to the development of modernism, a source not just of great music, as it had been for centuries, but also of great art, design, architecture, literature, science, and ideas.

Moriz and Hermine were patrons of the Secession, the group of artists, architects, and designers led by Gustav Klimt that broke away from Vienna’s long-established Künstlerhaus in 1897. They also were patrons of the Wiener Werkstätte, the most famous Viennese craft workshops, which the architects Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser established in 1903. The Gallias’ grandest, most striking painting was a full-length portrait of Hermine by Klimt. Five of the front rooms of their apartment in the Wohllebengasse were designed by Hoffmann. While some families were significant early supporters of this culture and others began relatively late, Moriz and Hermine were among the few who sustained their patronage while this culture was at its peak from 1898 until 1918. When Gretl and Käthe escaped in 1938, they took most of what Moriz and Hermine had collected and commissioned. Their crates, filled with the contents of Good Living Street, contained the best private collection of art and design to escape Nazi Austria.

Their destination was a Sydney apartment block built, like so many in the city, as if design did not matter, architecture did not pay, and aesthetics were for somewhere else. Its materials were the usual local combination of dull liver-red bricks topped by garish terra-cotta tiles. The approach to the front door down a narrow path on one side of the building was awkward, just as the main staircase was cold and mean. The building’s one notable feature—its view of the harbor stretching almost from Sydney Heads to the center of the city at Circular Quay—owed everything to nature and nothing to culture.

Wohllebengasse 4, c. 1913. (Illustration Credits ill.1)

The Gallias’ apartment was different. One of the iconic portraits of Gustav Mahler, an etching by the Secessionist Emil Orlik, hung in the apartment’s hall. The rest of the apartment’s walls were thick with Secessionist paintings—most notably, Klimt’s portrait of Hermine—while the apartment’s rooms were filled with Hoffmann furniture, rugs, silver, and glass. A small sunroom was crammed with a suite of white-and-gold Hoffmann tables, chairs, and display cabinets. The other rooms were a domain of black—almost everything in them ebonized so the grain of the timber shone through. There were black Hoffmann tables, chairs, si

deboards, and clocks, a black Hoffmann showcase, lamp, and piano stool, and seven black glass-fronted Hoffmann bookcases, which lined the walls of the two bedrooms as well as the long stretch of hall leading to the bathroom and toilet.

Because Hoffmann saw himself as creating a total work of art, or Gesamtkunstwerk, in which every element was integral and could fit into only one slot, his work could never be completely transplanted from one building, let alone one hemisphere, to another. Yet Gretl and Kathe—as Käthe became in Australia, just as Annelore became Anne—came remarkably close. For over thirty years, while the apartment in Cremorne was home to the Gallias, there was no comparable apartment in New York, Zurich, London, Budapest, or Prague. Nor, for that matter, was there one in Vienna itself, since most other Hoffmann interiors had been destroyed or dispersed. The apartment’s contents were a mover’s triumph, one of the great pieces of fin de siècle Vienna transported to Botany Bay.

I first went to the apartment as a baby—taken there by Anne shortly after she gave birth to me in 1957—and was soon going there regularly, usually with my older brother, Bruce. While adults who visited the apartment remember it as claustrophobic because the rooms were so full and so much of the furniture was black, I was completely at ease there as a boy. I had no idea that many of Gretl’s and Käthe’s things were designed for rooms at least two or three, if not four, times the size, rooms with high ceilings that easily accommodated chandeliers, rooms with fluted columns and marble paneling identical to those on the furniture, rooms designed at least as much for entertaining as for family life, rooms serviced by maids in uniforms. While I knew that Gretl and Kathe had fled Austria as refugees, I never thought of their things as being displaced. I thought everything in the apartment was in the perfect spot, exactly where it always had been intended.

Insofar as I realized there was a family treasure trove, it was not the apartment, where the doors had simple locks and Gretl and Kathe paid no attention to security, but a bank deposit box in a vast marble-clad, mosaic-decorated, barrel-domed vault in the center of the city where Gretl and Kathe kept their best jewelry in a safe twice the standard size. When I went there with Gretl, I looked with awe on the uniformed security guards, the grilled entrance opened only on proving one’s credentials, and the immense steel door. I was impressed that it required two keys to open the safe—one carried by the guards, the other by Gretl. I was struck by the serious quiet of everyone who entered and how they each looked to find a cubicle where they could change the contents of their safe without anyone else observing what they were doing.

Good Living Street

Good Living Street Two Afternoons in the Kabul Stadium

Two Afternoons in the Kabul Stadium