- Home

- Tim Bonyhady

Two Afternoons in the Kabul Stadium Page 10

Two Afternoons in the Kabul Stadium Read online

Page 10

Cheen’s inclinations were liberal. ‘We have to have some striptease shows and some night clubs in this city,’ he contended. But following the outcry over the Iranian movie Yusuf Zulaikha and claims it should never have been released, Cheen and his fellow censors cut and banned many more films. They included The Horseman, Hollywood’s one new movie about Afghanistan, based on the bestselling novel about buzkashi by French writer Joseph Kessel. When the Afghan government funded the local filming of some scenes, the arrival in Kabul of the movie’s Egyptian-born star, Omar Sharif, sent the waiting ‘miniskirted girls into shrieks of admiration’. But the censors cut the scene in The Horseman where Zareh ‘the untouchable whore’, played by Leigh Taylor-Young, undoes her belt, takes off her top and is seen from behind with a glimpse of her breasts. As Cheen described it, ‘Leigh Taylor is seen unbuttoning her vest to permit Omar Sharif ’s sexual advances. What should a censor in Kabul do with this kind of scene? Nude bosoms can not be permitted to be screened.’ The male body was much the same. In a film that showed soldiers in a shower, their ‘nude backs all had to be cut’.

The miniskirt remained a potent symbol. The censors allowed a modest version of it in Afghan Film’s second full-length feature, A Mother’s Behest. The film was applauded in Kabul and Jalalabad for its exploration of the relationship of a young middle-class couple whose enthusiasm for the modern was exemplified by his choice of a suit and hers of a miniskirt. When a group of American volunteers with the Peace Corps celebrated Christmas together in 1971 with a short performance adapted from Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, the ghost of Christmas past was ‘of course’ dressed in a chadari, and the ghost of Christmases future in a miniskirt. ‘We all laughed until we toppled off the cushions,’ one of the volunteers wrote, ‘our sides aching!’

CHAPTER 10

The Artist who Did Nothing

Most foreigners who visited Afghanistan in the 1960s and 1970s went only once. Five days was the average stint for those who came by air, ten days for those who travelled overland. Alighiero Boetti, one of Italy’s foremost young artists, was different. After flying to Kabul in March 1971, thirty-year-old Boetti stayed a month, then returned for another month that October, and continued these visits across the decade. While hashish and heroin drew Boetti to Kabul, so did Afghan embroidery. When he first arrived, many shops in the Shahr-e Naw were selling it, as were street vendors and government handicrafts shops at the airport and the Intercontinental Hotel.

Boetti was known for sculptures constructed in the simplest ways out of the most basic materials, whether by stacking concrete beams or arranging PVC tubes, as part of the Italian movement known as Arte Povera. But Boetti also saw himself as the artist of two works that he conceived and his wife, Annemarie Sauzeau, embroidered. When Boetti first visited Kabul, he commissioned three small pieces, providing short Italian texts which the embroiderers reproduced within a traditional setting of flowers and zigzag borders. Again, Boetti considered himself their artist.

Boetti returned with Sauzeau that October to visit Bamiyan, Afghanistan’s most celebrated ancient site, renowned for the tallest Buddhist sculptures in the world. Boetti also secured a place to stay in Kabul during his visits to Afghanistan each spring and autumn. Again, he commissioned embroideries, but much bigger ones based on world maps. While several other foreigners visited to buy or commission textiles, only Boetti thought of his commissions as contemporary art. As western curators, critics and collectors embraced them, these embroidered maps became the art made by Afghans in the twentieth century to receive most international attention, with Boetti taking the acclaim and proceeds.

Buddhism was Afghanistan’s dominant religion when monks at Bamiyan carved a thirty-eight-metre-high Buddha into the cliffs in about 500 CE and then a fifty-five-metre-high Buddha around 550 CE. When Afghans began embracing Islam in the seventh century, they left the Buddhas intact. But at some point the heads of the Buddhas suffered significant damage. One possibility is that, when Genghis Khan conquered Bamiyan in 1221, his men destroyed the Buddhas’ foreheads, eyes and noses as part of larger iconoclasm in the area. Alternatively, if the Buddhas’ faces were originally wood or metal rather than stone, as often conjectured, they may have disintegrated with age. Otherwise, the Buddhas largely survived—sometimes lauded by Afghans as ‘one of the marvels of the world’, but sometimes dismissed and denigrated because they were not Islamic and because they represented the human form.

This mixed response to the giant Buddhas in particular, and Afghanistan’s Buddhist heritage in general, was particularly apparent in the 1920s and 1930s. King Amanullah embraced Afghanistan’s Buddhist past when he established a National Museum that displayed many Buddhist sculptures. But Bacha Saqqao, who ousted Amanullah, identified the museum’s Buddhist sculptures as ‘idols’ and Amanullah as an ‘idol-worshipper’. When Nadir Khan in turn ousted Baccha Saqqao, his government issued a series of postage stamps depicting Afghan monuments including Bamiyan’s bigger Buddha. Because they were the first Afghan stamps to be pictorial, rather than carrying geometric designs or calligraphy, all were controversial, but the Bamiyan stamp was particularly so, prompting its withdrawal, even though the Buddha was only partially shown.

Westerners were also divided over the Buddhas. ‘Neither has any artistic value…Their negation of sense, the lack of any pride in their monstrous flaccid bulk…sickens,’ British writer Robert Byron maintained in 1937 in his prize-winning travel book Oxiania. Freya Stark, another noted British writer, concurred more than thirty years later. But French archaeologists, who received a monopoly to work in Afghanistan from Amanullah, promoted Bamiyan in a guide published in both French and German in the 1930s and sought to protect it. Nancy Wolfe, later Nancy Dupree, who wrote a series of English-language guides to Afghanistan for its Tourist Organisation from the early 1960s, lauded Bamiyan for ‘the most spectacular images of the Buddha ever devised’, ‘the embodiment of cosmic man’.

Foreigners who wanted to see more than Kabul typically started with Bamiyan, where the government had built a small hotel in the 1930s and the Tourist Organisation opened a prefabricated six-room motel imported from Finland in 1966. Three years later, if the guests of Kabul’s Intercontinental Hotel did not want to leave its five stars, they could go to its third floor where Amanullah Haiderzad, head of the Art Institute of Kabul University, created a sculpture reproducing one of the Buddhas using Bamiyan mud. If they wanted to see original material from Bamiyan, they could visit the National Museum where four rooms were devoted to Buddhist objects, while just one was devoted to Islamic material, implicitly treating it as of modest interest.

If these tourists wanted to visit Bamiyan and stay there, they could enjoy new accommodation in the wake of The Horseman, which was filmed partly at Bamiyan, prompting the government to build a village of fifty circular tents based on Tajik yurts. After the movie’s cast and crew left, the government opened these tents to tourists. Although mice infested their roofs, they proved popular, combining the traditional with ‘the usual amenities expected by the international community’, namely their own bathrooms offering hot and cold water.

Australian writer Murray Sayle, who hitched a ride on a vegetable truck, was ‘glad of armed guards…after a friendly warning that undefended vehicles were sometimes hijacked by opium smugglers, religious zealots and plain, old-fashioned bandits’. While buses cost little, they left Kabul at 3.00 each morning and took twelve hours to cover the 160 kilometres because they often stopped and the roads were terrible. Afghanistan’s internal airline, Bakhtar, launched by the government in 1968 with tourism to Bamiyan in mind despite its dirt landing strip, took just forty-five minutes, so the return trip could be made in a day, but those who flew ‘missed much of what Afghanistan is all about’, one visitor observed. In October 1971, Boetti and Sauzeau hired a jeep with an Afghan driver, which probably cost more than the flight but meant they could see the country close-up and travel when they wanted.

They were

among 12,000 foreigners who visited Bamiyan that year—about forty-five a day between spring and autumn. Sauzeau would recall that, ‘apart from the immense double icon’ of the giant Buddhas, ‘there was nothing and no one there’. While some visitors began with the smaller Buddha, most climbed only the bigger one because it was taller and the ascent was simpler through a chain of caves past niches with frescoes to the Buddha’s head. There they could look up and admire a fresco of Paradise showing the Buddha, enthroned Bodhisattvas and female musicians. They could also look out over woods, fields, gardens and irrigation channels which, cliché had it, were like another Paradise or Shangri-La, especially wonderous after brown Kabul and the barren mountains of the Hindu Kush.

Boetti’s new home in Kabul was his own hotel, which he opened with Gholam Dastaghir, a young Afghan whom he met on his first visit. As described by Sauzeau, the process was simple: ‘Just go to the only real-estate broker in the capital, well dressed and carrying your passport. After visiting the location, agree to rent it for a few years, cash up front; then a signature, a glass of tea, and the keys are yours.’ Boetti and Dastaghir did so, renting a bungalow in the Shahr-e Naw which they opened as a hotel just ten days after leasing it. Boetti expressed his interest in Afghan textiles when he thought of naming it ‘Gilim Hotel’ after flat-woven ‘kilims’, but instead called it ‘One Hotel’. Drugs were part of its service. Boetti described arriving there to be greeted by the hotel’s waiter with a ‘super hashish cigarette’.

One Hotel was at the centre of the modern in Kabul—just behind Afghanistan’s first supermarket, which was as renowned for being air-conditioned as for its tinned and plastic goods. While Boetti displayed typical audacity in claiming One Hotel as part of his ‘creativity’, it was a standard part of the tourist trade. Each morning it touted for business among new arrivals in the city as they alighted at its central bus station. For six months, it advertised its ‘luxury rooms’ with ‘modern bath rooms’, ‘always at your service’, in the Kabul Times.

The works that Boetti wanted to commission were world maps based on those in scholastic atlases. Having created a Political Map of the World in banal fashion in 1969 by simply colouring in the flags on a map he found in a junk shop, Boetti decided to have such maps embroidered, probably unaware that Iranian and Turkish weavers had made rugs based on world maps for at least a century. Before leaving Rome, Boetti had an assistant transfer maps onto three pieces of linen and mark each country with the colours and symbols of their flags. When Boetti arrived in Kabul, he delivered these materials to a local workshop. The biggest was to be two metres by three-and-a-half metres.

The status of embroiderers was generally low, like that of carpet weavers. They also typically remained anonymous, but embroiderer Zarghoona Adde featured in the Kabul Times in 1973 after one of its journalists took two foreign friends to see her work in Kandahar. He reported that, having married aged seventeen, Adde had five children before her husband died when she was twenty-four, leaving her near destitute, with embroidery her only income. Thirty-five years later, though her eyes were failing, she was still creating beautiful blouses and waistcoats. When the journalists’ friends sought to reduce her price, Adde exclaimed: ‘Embroidery is an art that uses the totality of an individual for its preparation. It should be appreciated as such. If I say it is priceless, I mean it.’

Boetti never met the women who embroidered his Mappe. He seemingly did not care if, having had little or no education, they did not know what the different shapes in a world map represented. He wanted the embroiderers to follow his instructions, not draw on their own artistic traditions or display creativity. But he must have been aware—as recognised by his Italian artist friend Francesco Clemente, who travelled with him in Afghanistan—that the embroiderers’ artistry was vital to the maps’ visual interest and appeal.

One of the first did not go to plan. When Boetti went to collect it in the spring of 1972, he found ‘major’ flaws which he had undone and restitched. When he arrived in Rome, some people found the Mappe ‘too charming’. Others were ‘conceptually troubled’ because ‘at that time not many artists had their works made by artisans’. Yet key figures in the modern art establishment embraced these embroideries. Italian critic Tommaso Trini put one on the cover of his influential new magazine, Data. Swiss curator Harald Szeemann reproduced it in the catalogue of Documenta, the renowned avant-garde art exhibition in the West German town of Kassel, which attracted attention even in Kabul.

Other foreigners also found Afghanistan a fabulous place for procuring textiles, old and new. As often happens, disaster fuelled the market, resulting in a mass of material being sold by the desperate to the profit of dealers. The drought of 1969–72 forced many Afghans to sell anything they could. As this material funnelled into Kabul, the city became the supplier of a cornucopia of artefacts, which local dealers supplemented with imports from Pakistan and India and material smuggled in from Soviet Turkmenistan. One Hotel was a small centre of this trade, accommodating both Indian and Pakistani carpet dealers.

Another guest was Vladmir Haustov, a leading American textile dealer who specialised in nineteenth-century pieces and first visited Afghanistan in 1970 with his partner Gail Martin. After initially working from their Manhattan home, Martin and Haustov established a gallery on Second Avenue, then moved to Madison Avenue. When Boetti and Sauzeau travelled to Tashkurgan, the site of Afghanistan’s only remaining covered bazaar renowned for its streets roofed with wood and wickerwork and spectacular tiled cupola, Haustov was their guide. Between admiring the bazaar, which was of such architectural and anthropological interest that rival Swiss and Swedish academics published books about it in 1972, Boetti was an eager purchaser of silk ikat, tie-dyed textiles with complex abstract designs.

The first shop in Europe to specialise in such material was on the King’s Road in Chelsea, made chic by Granny Takes a Trip. This outlet was opened by two young Englishmen, Tom Harney and David Lindahl, who called it ‘Oxus’ after the river separating Afghanistan from the Soviet Union. For six months each year, Harney visited Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan and Kashmir to buy material, while Lindahl ran the shop; then they reversed roles and Lindahl procured and researched textiles. Harney and he came to international attention in 1970 when the American edition of Vogue identified Oxus as ‘the best shop in London’, satisfying the ‘irresistible urge for the East that we all feel’.

Ira Seret, who had secured the first big consignment of pustinchas to reach Manhattan, fed this market too. In 1970, he appeared in Vogue as New York’s counterpart to London’s Oxus, wearing an antique purple silk caftan embroidered in gold and lined with silver-fox fur. When Seret assembled a collection of eighteenth-century Uzbek tent-hangings that he sold through Bloomingdales, he appeared there daily in a white robe and shawl. In between, Seret and New York designer-decorator Angelio Donghia commissioned Pakistani tent makers in Lahore to make modified wedding tents as exotic interiors for the homes of rich Americans. Seret also opened a factory in Balkh in northern Afghanistan, where he employed about fifty men and boys making the flat-woven rugs known as dhurries and silk ‘art rugs’, sometimes designed by Seret himself, for the American market.

Boetti’s ‘postal works’ were very different. He began in Europe by deliberately sending letters to wrong addresses and making art out of the returned envelopes. Then, he sent multiple envelopes addressed correctly, with the same stamps arranged in all possible permutations, and waited to see if letters would be lost, ruining the sequence. When Boetti initiated some from Afghanistan, the reputation of its postal service suggested this prospect was inevitable. Afghan postage workers were said to be so ill-paid and corrupt that they stole international letters so they might redeem their uncancelled stamps at face value. But senders could insist on having the stamps franked in their presence and Gholam Dastaghir, whom Boetti employed to do much of his mailing, possibly did so. Perhaps Afghanistan’s post worked better than cliché had it. Whatever the artistic sig

nificance of Boetti’s 720 Letters from Afghanistan of late 1973 and early 1974, it showed that a vast quantity of mail could reach Europe from Kabul.

Boetti also commissioned other forms of embroidery but the most successful were the Mappe. While Boetti once declared that he wanted to commission only one embroidered map, forgetting that he began with three, he went on to commission many more because of demand. The result was about 160 with Boetti’s contribution always a very limited part, as he described with delight: ‘I did nothing for this work, chose nothing myself, in the sense that: the world is shaped as it is, I did not draw it; the flags are what they are, I did not design them. In short, I created absolutely nothing.’

Boetti would make many claims for these embroideries, especially their impact within Afghanistan. As part of his inveterate self-promotion, Boetti maintained that embroidery in Afghanistan came ‘to a stop’ in the 1920s and only ‘started anew’ because of him. He also claimed that an Afghan carpet dealer in Milan had reported that rugs in the ‘Boetti style’ featuring maps had ‘become obligatory in Afghanistan’. Boetti exclaimed: ‘How about that! A guy from Turin like me who goes off to the uttermost ends of Asia and manages to have an influence on a tradition spanning thousands of years.’ These claims were baseless. As art historian Nigel Lendon has observed, ‘the suggestion of Boetti’s influence on indigenous carpet makers has no supporting evidence, outside of the rumours and assumptions made between Boetti and his close circle of friends, family, employees, dealers and the custodians of his estate’.

In Italy, a typographer designed and updated the Mappe as the boundaries of countries and their flags changed. In Kabul, Gholam Dastaghir commissioned the Mappe from two women, remembered only as Fatima and Habibah, who gave much of the work to members of Dastaghir’s own family. While their embroidery was not as fine, diminishing the maps’ visual interest, Boetti was happy to have cheaper ones produced more quickly. His prime involvement was to check the finished maps in Kabul. He gave the embroiderers some latitude only from 1978 when they used green, not blue, to delineate the oceans on a Mappa and, instead of requiring them to redo these sections, Boetti embraced their departure from his instructions as part of the creative process.

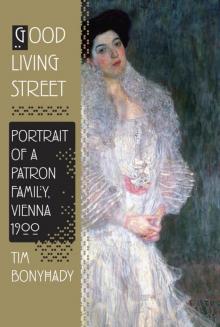

Good Living Street

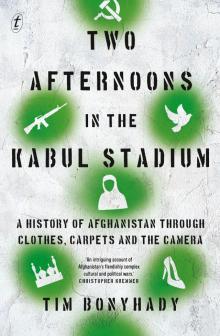

Good Living Street Two Afternoons in the Kabul Stadium

Two Afternoons in the Kabul Stadium